Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

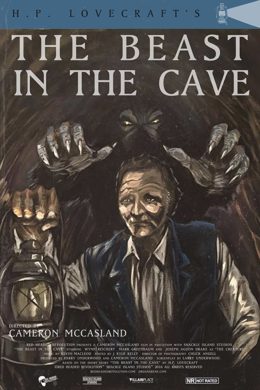

Today we’re looking at Lovecraft’s own “The Beast in the Cave,” written between Spring 1904 and April 1905, and first published in the June 1918 issue of The Vagrant. Spoilers ahead.

“Then I remembered with a start that, even should I succeed in killing my antagonist, I should never behold its form, as my torch had long since been extinct, and I was entirely unprovided with matches. The tension on my brain now became frightful.”

Summary

Our old friend Unnamed Narrator returns, only to find himself “completely, hopelessly lost in the vast and labyrinthine recesses of the Mammoth Cave.” It’s his own fault for wandering off into “forbidden avenues” while the rest of the sightseeing party sticks close to their guide; nevertheless, he congratulates himself on his stoic composure as his torchlight fails and starvation in the rayless dark looms.

Resigned to death as he is, narrator will neglect no chance for rescue. He shouts at the top of his lungs and hears his voice “magnified and reflected by the numberless ramparts of the black maze about” him. No one will hear him, he’s sure, so he starts at the sound of approaching steps. Is it the guide, come to find his errant lamb? But the guide’s booted steps would sound sharp and incisive. This tread sounds soft and stealthy, as if produced by the padded paws of a wild feline or other large beast. Besides, he sometimes thinks he hears the four feet, not just two.

To fall prey to a mountain lion might be a more merciful end than dragged-out starvation, but the instinct for self-preservation determines narrator to exact as high a price as possible for his life. He hushes, hunkers down, gropes in the blackness for rocks. The intermittent quadrupedal-bipedal locomotion of the beast disturbs him. What can it be, really? Some creature that was lost like him? That’s survived on eyeless bats and rats and fish? The guide earlier pointed out huts once occupied by consumptive patients who sought the cave’s pure air, constant temperature, and quiet for healing. Local tradition held that they’d suffered awful physical changes through long residence underground. Perhaps what stalks him has taken on a hideous new shape—and one he’ll never even see!

Narrator, so calm before, gives way to “disordered fancy.” He’d surely scream if he weren’t so petrified. Never mind—as the thing gets close enough for him to hear its labored breathing, his hysteria ebbs. Guided by his “ever trustworthy sense of hearing,” he pegs a rock at the creature and gets close enough to make it jump. Readjusting his aim to its new (jumped) coordinates, he pegs another rock and bam, flattens that sucker. Is it dead? For an moment he dares hope.

Nope, it starts gasping, wounded.

Superstitious fear seizes narrator. He runs in the opposite direction from the beast, in the dark, at full speed, until hallelujah, he hears boots and sees the torchbeam of the guide! He falls at the man’s feet and babbles out his terrible story. Then, emboldened by company, he leads the guide toward the downed beast.

It lies on its face, an “anthropoid ape of large proportions.” Snow-white hairs grows long and profuse from its head. The hands and feet, have long nail-like claws. There’s no visible tail. The overall pallor of the body, narrator ascribes to prolonged residence in the cave.

The guide draws a pistol to dispatch the still feebly breathing beast when it begins to chatter in a way that makes him drop the weapon. It rolls over, and they see its black iris-less eyes, its not-quite-simian face. Then, before it dies, the thing utters certain sounds. The guard clutches narrator’s sleeve. Narrator stands rigid, eyes fixed in horror.

“Then fear left, and wonder, awe, compassion, and reverence succeeded in its place, for the sounds uttered by the stricken figure…had told us the awesome truth. The creature I had killed, the strange beast of the unfathomed cave was, or had at one time been, a MAN!!!”

What’s Cyclopean: When the guide finally appears, Narrator gibbers. No surprise, after facing such “grotesque conjectures.”

The Degenerate Dutch: The MAN has degenerated into a simian beast all on his own, no ethnicity required.

Mythos Making: Transformation into white ape continues to be the unfortunate fate of many who turn from civilization, throughout Lovecraft’s stories.

Libronomicon: No books in the cave, but Narrator is prepared for this situation by a life of philosophical study.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Some people go mad when trapped in caves—but this end, Narrator’s certain, will not be his.

Anne’s Commentary

I remember, around the age of fourteen, writing Star Trek fan fiction and an epic novel (never to be finished, thank the literary gods) about an Earth taken over by the animals (all of ‘em, ants to elephants, plankton to blue whales) and this super animal whisperer guy with a pro-ecology agenda that didn’t necessarily include other humans apart from this one girl (my “stand-in”) who might also have super animal whisperer powers. Yeah. Sort of that Ren-Rey dynamic, come to think about it.

At fourteen, Lovecraft wrote “The Beast in the Cave.”

Poor young Howard. We mustn’t suppose that only the last two generations have produced those pinnacles of human intellectual evolution known as the natural fanboy and fangirl. Surely Howard too was born to binge-watch, to MMORPG and cosplay, to write the most celebrated tome-length works of pure canon and silly-ship-free fan fic ever LIKED in the aethereal halls of NET!

But young Howard had no TV or movie theater or laptop or cell phone. He did have books, though, and access to many more at local libraries. Bookwise, Poe was an early idol and powerful influence, who’ll show up to much better effect in such first-maturity Lovecraft tales as “The Tomb” and “The Outsider”; in “Beast in the Cave,” Poe permeates the diction and probably incites the odd bipolarity of the narrator, who one moment preens about his composure in the face of subterranean death, the next works himself into melodramatic frenzies of fear imagining the monster he’ll never see.

For his depiction of the Mammoth Cave, Lovecraft evidently did much research at the Providence Public Library. I like to imagine him walking there, notebook under his arm, earnest as an equally young Charles Dexter Ward, down College Hill, through the scruffy commerce by the river, onward toward the mystic west. Research turned up for him the tragic and true story of the consumptive colony in the cave. Interesting that the consumptives don’t figure more in “Beast.” Some think the beast itself is a survivor of their group, but I’m more inclined toward a lost explorer or hunter. If the consumptives left Lovecraft wondering how they might have fared if they’d survived for generations underground, changing, devolving, he would work that idea out later with the Martenses of “Lurking Fear.”

Reading, in Mammoth Cave’s case, didn’t give Howard the wherewithal to describe the scene vividly, to create the ominous atmosphere such echoing confines deserve. Or, as likely, his writing inexperience didn’t give him the craft to do so. Not fair, but the story must fall flat in comparison, say, to the immediacy and gripping suspense Mark Twain brings to Tom Sawyer and Becky Thatcher lost in McDougal’s Cave.

Last quick note, and the important thing: Lovecraft, at fourteen, is already writing of encountering the Other, in the Dark, and of terror that may shift into awe, even to compassion, as one recognizes something in the Other missed at first.

It’s a current in Lovecraft I want to explore in a lot more depth. A current so many of us swim and dive in, from shallow to deep and deeper, easing in, then struggling (it seems inevitable), struggling.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

A MAN!!! Oh, Lovecraftian all-caps drama, how I have missed you!!! Let’s have some more exclamation points—why stop at three??? I don’t judge, given that Howie’s juvenalia is miles beyond my own. He wrote this when he was 14, published it in an amateur zine when he was 28. At 14, I was writing cyberpunk assassins. No zines for those—they will NEVER SEE THE LIGHT OF DAY!!!

There’s something reassuring about well-telegraphed melodrama. Stoic rationalist lost in cave. Stoic rationalist faces mysterious beast. Stoic rationalist, with conveniently uncanny aim, kills beast with a rock. Rescuer arrives with revelatory flashlight. Flashlight reveals what the rationalist’s fate would’ve been—not the starvation he stoically predicted, but something far worse. Eating blind cave bats isn’t as great a strategy as you might think.

The prescience of Lovecraft’s juvenalia is startling. I mean, I don’t write many cyberpunk assassins these days, and haven’t in years—my obsessions have changed over the decades, as I suspect many authors’ do. But here in 1904 is the fear that, separated from the things of civilization, man degenerates. Later Lovecraft will write similar degeneration in family lines. The end stage is still, all too often, a white ape. Martenses turn into ‘em. Jermyns marry ‘em. They’re all over the place. Why white apes? Could we be just a little bit terrified that whiteness is not, in fact, a thing that confers superiority? In any case, it’s a particularly impressive transformation for a single individual—getting lost in a cave doesn’t normally cause massive changes in eye and limb structure, but perhaps they’re mutagenic blind cave bats.

I’m somewhat more sympathetic to young Lovecraft’s—and older Lovecraft’s–desire to write stoic rationalists. Kind of appealing for an anxious boy, and of course it provides more contrast when the narrator does lose it.

The setting may be the best thing about “Beast.” Mammoth Cave in Kentucky is one of the longest cave complexes in the world, a great place to get lost. Caves inherently carry Lovecraftian attraction/terror. People explore them deliberately—and like our narrator, are drawn by curiosity too deep and too far from the surface and safety. Labyrinths hidden forever from the sun, full of inhuman forms, where one mistake can easily mean your life. They may hold the ghosts of ancient lizards. Or mad scientists. Or albino penguins. That they should have the power to change people seems… reasonable. Beyond the apey imaginings of a 14-year-old, there are all sorts of terrifying possibilities.

I do like that we never learn what sounds revealed the beast’s true nature. Laughter? Crying? Words? Human vocalization is pretty distinctive. I wonder how beast-like the “beast” actually is. We don’t see any evidence that he actually means Narrator harm. He hears a human voice calling, for the first time in years, and goes toward it. Only to be felled by Narrator’s missile. Who, then, is the real beast? The story gets as far as compassion, but doesn’t ascend quite so far as regret.

Final thought: it’s great that a life of philosophy prepares one to face death with cool and rational opposition. But what do you have to study to keep yourself from wandering off without a guide thread in the first place?

Next week, George T. Wetzel’s “Caer Sidhi” provides another tale of uncanny transformation. You can find it in the Second Cthulhu Mythos Megapack.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots (available July 2018). Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.